The first black president of an Ivy League institution, and first female president of Brown University, Ruth Simmons is well-known for her readiness to speak out. Throughout her career in academia, she’s been committed to campaigning on behalf of underrepresented or unequally treated groups, and shown she’s not afraid to tackle contentious issues head-on.

So she seems well-placed to advise on the question of when universities should take a public stance. In the midst of so many contentious and often emotive social issues, when should higher education institutions get actively involved in social change and moral questions?

Should universities remain “ivory towers”?

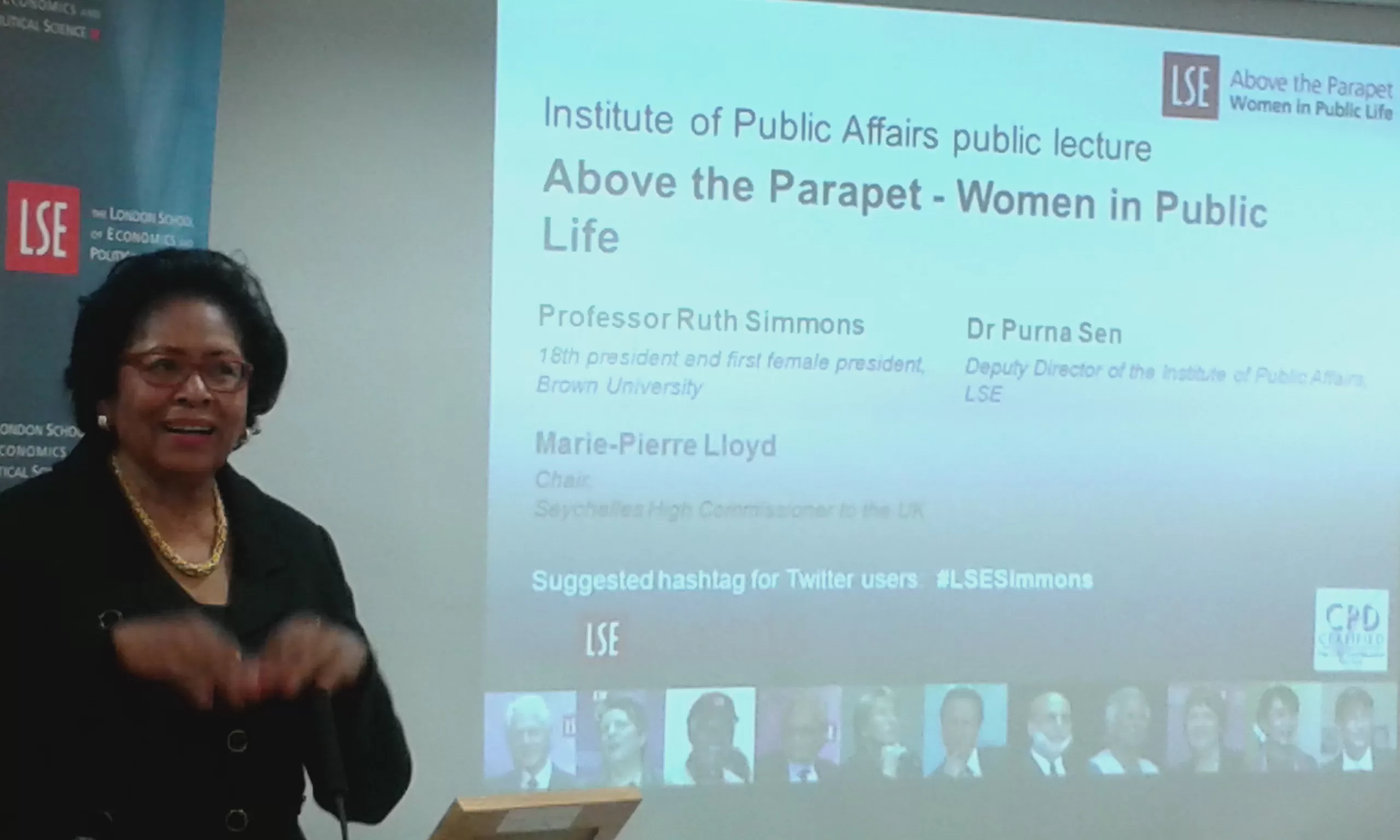

This question was put to Simmons at a public event yesterday, where she was speaking as part of LSE’s Above the Parapet series. Should universities remain “ivory towers”, or should they speak out from their platform of perceived authority?

First, Simmons noted, universities can’t avoid being involved. They are part of our societies, and they teach values in many ways – through the types of program they offer, for example.

Next, she acknowledged that it’s not practical or necessary for universities to issue a public statement every time the media headlines change or a campaign reaches high-pitch. Having served as a university president for 17 years – at Smith College from 1995 to 2001, and then at Brown until 2012 – she’s adept at saying “no” to comment requests.

But having made this point, Simmons emphasized the importance of speaking out on the really important things – “issues of overriding importance”. This is especially important on issues of human rights, she said, giving the example of LGBT rights as one such contemporary concern.

Challenges and rewards of being “the first”

Despite her proven willingness to take on divisive topics, Simmons said that if she’d known in advance what was in store during her Brown presidency, she’d probably have turned down the position.

While still new to the role, she faced the challenge of responding to a series of law suits which suggested the founders of Brown had been directly involved in the slave trade – an issue close to her own heart, as she is herself descended from slaves.

She responded by establishing a committee of students and faculty members, tasked with uncovering the truth about the university’s well-buried past. Initially, she and the group faced much criticism, scepticism and even personal insult. But the resulting report, recommendations and dedicated research centre were ultimately met with widespread praise, with a similar approach being adopted as a model by institutions across the world.

Similarly, Simmons recalled the challenges she faced earlier in her career, when campaigning for more inclusive faculty recruitment practices. Again, her determination was eventually rewarded – leading to recognition for both herself and her institutions, and setting an example for wider change across the sector.

On a more personal note, she spoke about the challenges she faced in being “the first” – the Ivy League’s first black president, Brown’s first female leader, and additionally defined by her upbringing in a poor, Southern, racially segregated setting. While indulging in a “fantasy” of being able to operate just as herself – apart from all these labels – she acknowledged that the challenges she’s faced as a result of her minority status may well have made her an even better leader.

Undoubtedly, Ruth Simmons’ own willingness to speak out and drive change has left the universities she’s been part of stronger and braver too, setting a precedent for the pursuit of more just, open and inclusive institutions and societies.

Follow us on Twitter for more higher education news and comment.